select installations

Everywhen - Immersive Album Experience at Phi Centre // IMAX // Cineplex

There are just three sounds found on Everywhen, the new album from Canadian wildlife recordist, composer, and vocalist Jonathan Kawchuk: the human voice, sine tones from a synthesizer, and the Rocky Mountains near Kananaskis, Alberta. Recorded painstakingly in Dolby Atmos, it is the product of six years of direct relationship with the trees, stones, streams, grasses, grizzly bears, birds, rabbits, elk, and all other things that call the enormous, humbling mountains home. It is a harsh, anxious, tactile, heavenly, collage-based work of found sound and vocals, of breath and wind and space. It is at once deeply unsettling and supremely calming. It is inspired by and carries the philosophies of athleticism, transcendental black metal, and the unfeeling amorality of nature. Everywhen is not a record about a place. It is a record by a place.

I-Thou

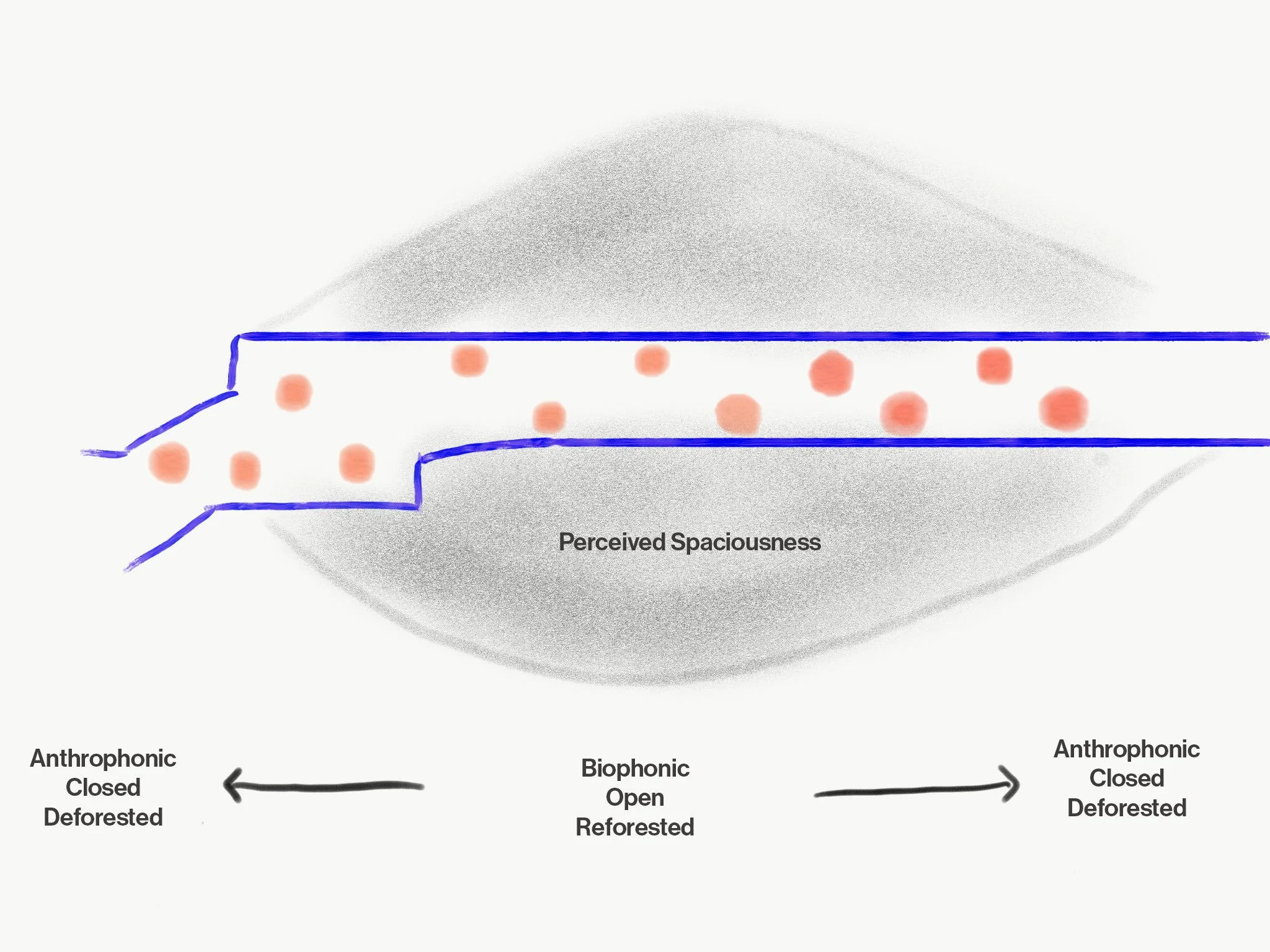

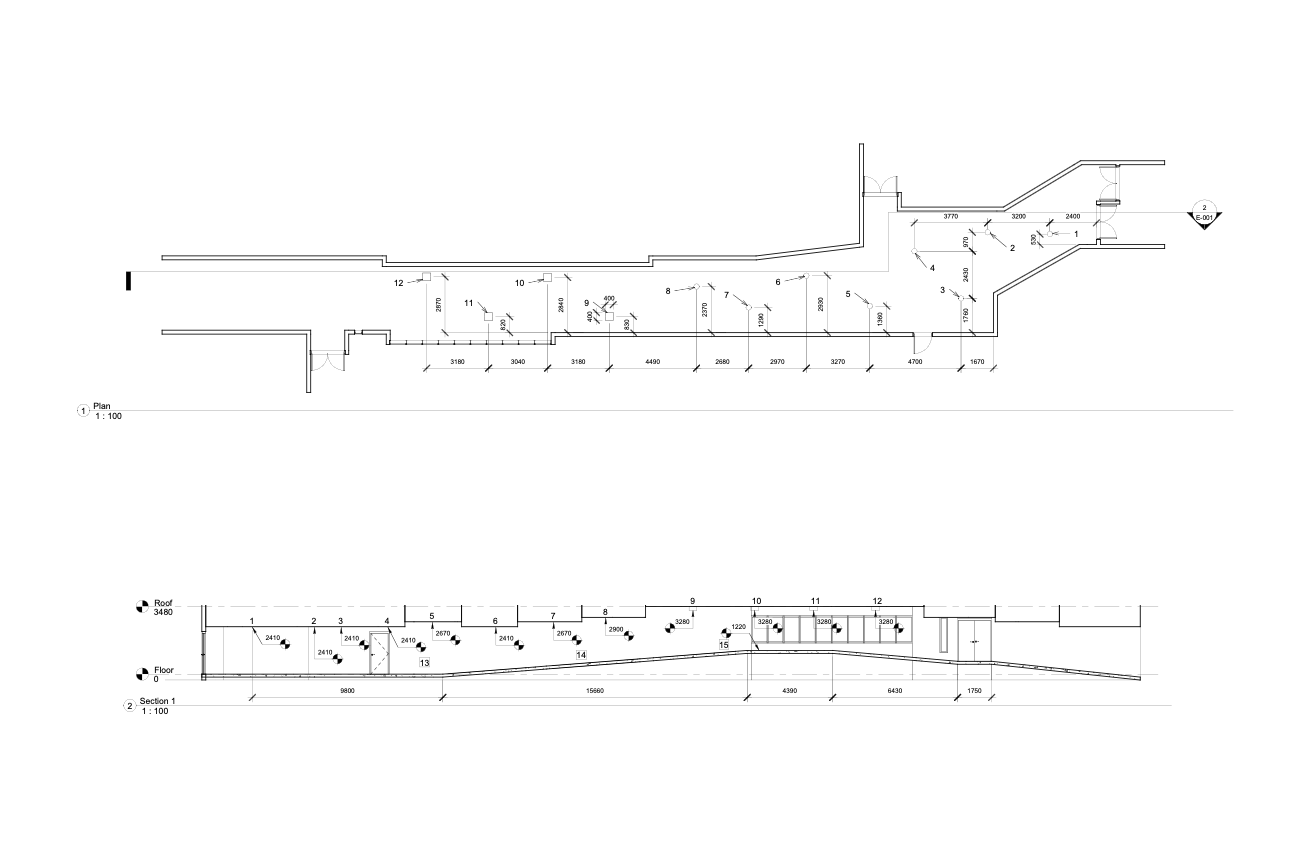

In I-Thou, individual sounds move down the hallways at 1.4m/s, the average walking speed of a person. This means that a listener will generally have the same sound to guide them throughout the hallway. It also means that each listener will have a different sound each time they enter the +15, depending on when they begin walking. As the sound and listener approach the centre of the hallway, the sound becomes more reverberant. This “reverb” is actually a 3D acoustic echo of a real forested space in local Kananaskis country - the first recording of its kind.

The auditory illusion of walking into the more reverberant centre of the hallway is that the space will sound much larger and much more open than it actually is. Psychoacoustically, this means that listeners will subconsciously recognize this as an outdoor space. For a moment, a place that has been clear of primary flora for over 144 years (downtown Calgary) will feel sonically “reforested”. As people walk through, they are guided out in the same way.

Desire Paths

My work as a composer and sound artist stems from the young but vibrant tradition of ecomusicology: the study of music at the intersection of culture and the environment. I am fascinated by how the music and sound we create can interact with—and stem from—the natural world, rather than simply mirroring the sounds and structures we hear within it.

When sound interacts with and reverberates through a natural environment, it takes on the characteristics of that space, much like an echo chamber. The parallel field of acoustic ecology examines an environment’s relationship to sound as a way of understanding the health of ecosystems. Working with acoustic ecologists, outdoor 3D capture techniques, and sound installation allows me to bring the experience of some of the world’s most threatened environments to an audience.

// Seismic Lines

Created by the energy industry for oil and gas exploration, seismic lines are both corridors and forms of anthropogenic disturbance. Woody vegetation is removed to create linear openings in the forest, fragmenting habitat across vast areas. These lines are pervasive throughout the region, particularly in Alberta.

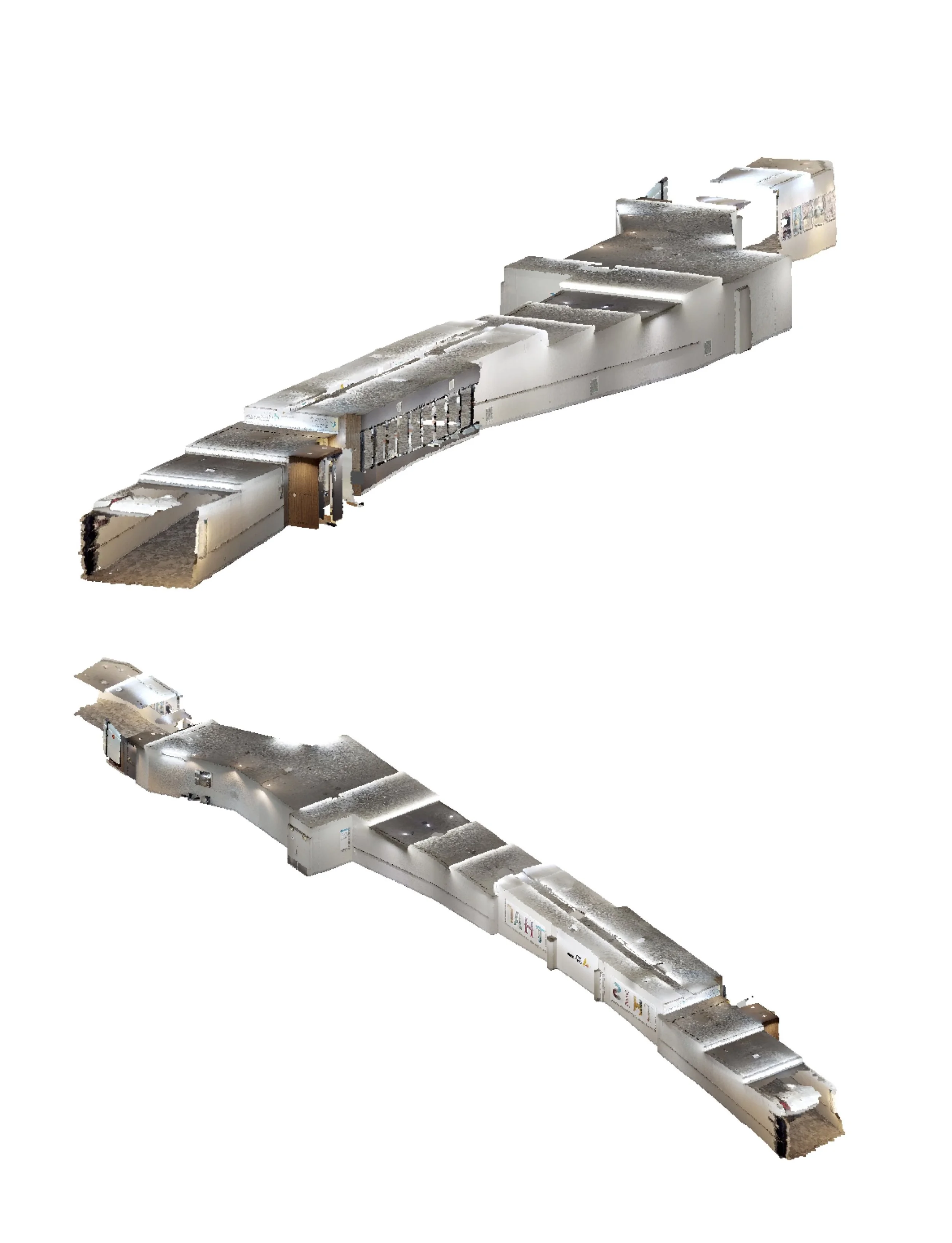

// The Mic Grid

Richard Hedley is a biologist formerly affiliated with the University of Alberta’s Bayne Lab. Part of his work involves monitoring behavioural changes in bird populations around seismic lines in Northern Alberta. Poetically, the most effective way to do this is by deploying a massive grid of sound: 25 synchronized microphones, each spaced 300 metres apart, recording simultaneously.

// Immersion

In this work, you will hear 26 square kilometres of sound compressed into a single hallway. Bird flight patterns, storms rolling in, and wind sweeping across the entire grid race along the +15, alongside aircraft, logging trucks, and other disturbances that threaten the area.

Kelp Reverberations

Trying to record the sound of the ocean is like trying to make your favourite childhood dish for a friend. So much of the charm is neither the mac nor the cheese, but all your sense memories that flood back. Perhaps your friend does not share these same memories, and so the meal falls flat without the added spice of shared experience. The sound of the ocean is as subjective an experience. Any field recordist will tell you that sticking a microphone faithfully in front of the sea will produce a result that is anything but faithful. Often, it doesn't sound like the ocean at all. The sound of the sea is the sound of the "ocean of our mind", and the microphone, or what recordist Lawrence English might call the prosthetic ear, is anything but an honest replacement of our own. Our ears are tied to a personal memory bank, and so field recordists often blend multiple recordings to create a collage that feels like the real deal. An objectively inaccurate process to create a subjectively accurate result.

To me, this means that even more musical or impressionistic renderings of the ocean are fair game. John Luther Adams' symphonic Become Ocean is no more or less subjective or accurate than Chris Watson's field recorded Glastonbury Ocean Soundscape. For our part, we tried to make our dish out of strange and hard-won ingredients. Alpenhorns made from bull kelp (from musician Daniel Lapp), cetacean recordings from research conducted nearby (Monika Wieland Shields of the Orca Behaviour Institute), and a whole bunch of other sounds we beachcombed for.

Ocean waves give us almost entirely white noise, which is a technical challenge and a poetic opportunity. White noise, consisting of all frequencies at equal intensity, contains somewhere in it all words that have ever been spoken, all songs yet to be written, all attempts at sonic reconstruction. Somewhere in the white noise of the next wave you hear is our installation, as well as everything else. The sound of the ocean is an exquisite corpus of all-sound, which renders every interpretation as accurate in spirit, subjective in execution, and a total failure in recreation. The ocean will forever evade captivity.